Enjoy the RSO!

Since you can’t see us, HEAR US! During this time of cancelled performances and restricted gatherings due to health concerns, the Ridgefield Symphony Orchestra invites you to enjoy some of our past performances as we look forward to bringing you more great live music in the not too distant future! Scroll down to hear all the posted pieces, and please also enjoy the program notes for each piece.

Paul Frucht – Dawn

Paul Frucht – Dawn

RSO, October 2017 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Yuga Cohler, Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Paul Frucht (1989 – ) – Dawn

(Dawn Hochsprung was the principal at Sandy Hook Elementary School who gave her life trying to protect her students and teachers when she confronted the armed shooter who barged into the school on December 14, 2012.)

Dawn Hochsprung was an incredible person I had the fortune of meeting as a student at Roger’s Park Middle School from 2000-2003 where she was an assistant principal. I worked with both her and her husband, George, as a member of National Junior Honor Society. When the tragic events occurred at Sandy Hook Elementary School, I, like everyone else in the Danbury area, was shocked and deeply saddened. The Hochsprungs had always stuck out in my mind as not just outstanding teachers, but some of the most caring, genuine, and positive people that I had come across during my time growing up in Danbury. I felt immediately compelled to write something for Dawn’s family and also for the other families who lost loved ones.

I titled the piece “Dawn” not simply because it is dedicated to her, but because the nature of Dawn’s actions on the day of the shooting are the inspiration for the character of this piece. When she became aware that her school was in danger, her immediate response was to protect the children. She put herself in harm’s way in an entirely selfless act in an effort to save the lives of her students. Her legacy is one of selflessness, positivity, and extraordinary courage. This piece celebrates that legacy. Program notes by Paul Frucht.

____________________

Igor Stravinsky – Rite of Spring

Igor Stravinsky – Rite of Spring

RSO, May 2019 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Yuga Cohler, Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) – Rite of Spring

A riot broke out at the Paris premiere of Stravinsky’s ballet The Rite of Spring in May of 1913, complete with loud vocal protests, violent arguments, and fistfights. It was a war over art – or at least over the nature of music. Only after subsequent performances, where there was sufficient order to permit the music to be adequately heard, could there be a growing awareness of the staggering artistic effect that what many regard as the twentieth century’s most influential musical work would have. The unprecedented sustained dissonance, violent and kaleidoscopically shifting rhythms and harmonies, and the clashing chords tempted some composers to move backward into frank Romanticism or even (oddly enough, Stravinsky himself!) into neoclassicism. Others, though, embraced the newness and even imitated it, thus freeing music to express every aspect of human experience.

Stravinsky’s collaboration with the Russian painter and stage designer Nicholas Roerich, who was also an archaeologist, persuaded the comp0ser to conceive the work (whose Russian title really comes closer to meaning “Sacred’ Spring than The “Rite” of Spring) as a series of images involving ancient Slavic rituals to welcome and bless the spring, including an old witch who predicts the future, a tribal elder who kisses and blesses the earth, and a dance of young virgins who choose one of their number to sacrifice herself to the god of spring by dancing until she dies from exhaustion.

The first of the two main sections, The Adoration of the Earth, opens with the mournful sound of a Lithuanian folk tune, intoned in the high register of a solo bassoon. Dance of the Adolescents, which follows, is built on massive repeated, dissonant chords and a monotonously repeated ostinato – both such unchanging harmony and repeated figures (used by Stravinsky throughout the work) being characteristics of primitive folk music.

Game of the Abductionis a breathless onrush, broken into by abrupt, irregularly spaced chords from the full orchestra, and Spring Rounds and Games of the Rival Cities both feature simple melodies within a very restricted range (also characteristic of primitive music), the first given out in parallel chords over a droning bass and the second over thunderous orchestral outbursts.

The Entrance of the Celebrant is heralded by an austere theme for four horns in octaves, with a brief dissonant passage denoting the Adoration of the Earth. The first part’s concluding section, Dance of the Earth, reaches fever pitch, with loud tympani and bass drum counter rhythms supporting wild figurations in the violins and powerful off-beat chords in the winds.

The second part opens with an Introduction, followed by the Mysterious Circles of the Adolescents, with a mournful theme moving from violins to horns and then to oboes, and with atmospheric effects provided by strings divided into thirteen parts.

The Glorification of the Chosen One is pure percussive rhythm, with frequent changes of meter, and the Evocation of the Ancestors, without a change in tempo, is enlivened by swelling pulsations from the tympani and fanfare-like utterances from the winds. The slow Ritual of the Ancestors moves from a gentle accompaniment to a full orchestral outpouring, with a strong and heavily moving theme for horns that falls off sharply towards the end of the section.

The conclusion – Ritual Dance of the Chosen One – is the loudest and most rhythmically elaborate segment of the work, projecting an almost painfully sustained atmosphere of tension and energy bordering on violence. Program notes by Courtenay Caublé

____________________

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Overture to Don Giovanni, K527

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Overture to Don Giovanni, K527

& Divertimento in E-flat Major, K113

RSO, March 2018 Concert, The Ridgefield Playhouse

John Cuk, Guest Conductor

Overture to Don Giovanni, K 527

Divertimento in E flat Major, K113

PROGRAM NOTES

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Overture to Don Giovanni, K527

Unlike Brahms and other composers who often labored for months or even years of the composition of a single work, Mozart composed with lighting speed conceiving a work entirely in his head before committing it to a score.

Mozart’s wife Constanze provided us with the best evidence we have of Mozart’s astonishing composing technique in an anecdote she told her second husband, George von Nissen, who was writing a biography of Mozart’s life and career. According to Constanze, on October 28, 1787, the day before Don Giovanni was to receives its premiere performance in Prague Mozart still had not composed an overture for the opera. So, kept alert by having Constanze telling him funny stories, Mozart set to work. Well in to the night he dozed off in exhaustion; but Constanze was able to rouse him after a couple of hours, and he miraculously finished the score before the copyists arrived on schedule in the morning at seven.

The opera’s storyline involves the dissolutely amorous (but amusing) adventures of Don Giovanni, who is eventually confronted and threatened by the ominous graveside stature of the father of one of his victims. His response is to laugh at the statue and invite it to dinner. The opera’s climax occurs when the statue, as promised, appears at the dinner and drags the unrepentant scoundrel down to Hell.

Although the overture contains no recognizable thematic bits from the opera, the music expressively reflects the story’s essential elements of joviality, conflict and imposing doom and suggests the underlying presence of the supernatural.

A slow and rather threatening introduction in the key of D minor, a key that Mozart and his contemporaries associated with dramatic conflict and doom, musically foreshadows Don Giovanni’s retributive fate, with crashing D minor chords that could suggest the threatening statue and rather spooky scale passages perhaps suggestive of the presence of the supernatural.

The, with a tonality shift from D minor to the cheerier key of D Major and a tempo shift to allegro, the remainder of the overture is playful and full of life, evocative of Don Giovanni’s impetuous self-consciousness and his amusing exchanges with his servant Leporello.

Unlike the overture’s original version, which had not ending but just moved quietly into the opera’s first scene, the concert version ends the overture in a splash of enthusiastic orchestral color. Program Notes by Courtenay Caublé

Divertimento in E-flat Major, K113

- Allegro

- Andante

- Menuetto – Trio

- Allegro

A Divertimento is an instrument composition with several movements and a combination of instruments, with each part played by a single performer rather than with several players on a a part, as in the first and second violin sections of a symphony.

Mozart composed Divertimento in E-flat Major, K113 in 1771, when he as only fifteen, during his second childhood trip to Italy with his father Leopold; and Leopold’s handwriting at the top of the scores suggests that he may have taken a hand in composing the pieces, as he often did for his gifted son’s early compositions.

With concertante parts for pairs of clarinets and horns, it was the first work in which Mozart used the clarinet, which quickly become one of his favorite instruments. Three years later, though, he had to revise the score to include a pair of oboes, to be used in place of the clarinets for performances in places like Salzburg, where players of the relatively new clarinet were unavailable.

The first movement (Allegro), in compact sonata-allegro form, moves along cheerfully, with playful conversational exchanges between winds and strings. Mozart’s fondness for myriad attention shifts from one instrument to another, not quite yet honed to perfection, sometimes overly fragments thematic flow, but the overall effect is pleasantly entertaining.

The second movement (Andante) begins with a tranquil theme played by the clarinets with echoing response form the horns over a low string accompaniment. A brief bridge passage then leads to a repeat of the thematic material with developmental embellishments.

The Menuetto is a jauntily dancelike, with a contrasting lyrical Trio segment in a minor key.

A sprightly three-note “motto” initiates a rondo in the final movement (Allegro) in which the motto periodically return to punctuate the lively lyrical flow. Program Notes by Courtenay Caublé

____________________

Johannes Brahms – Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

Johannes Brahms – Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

RSO, December 2016 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Kevin Fitzgerald, Guest Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) – Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68

- Un poco sostenuto – Allegro – Meno allegro

- Andante sostenuto

- Un poco allegretto e grazioso

- Adagio – Più andante – Allegro non troppo, ma con brio – Più allegro

Brahms was so convinced during his early career that that no one could ever hope to go beyond or even to equal the great Beethoven’s achievements as a symphonist that he protested to his friends, in spite of their encouragement, that he would never write a symphony. So, ironically, it was only after being moved to tears on hearing a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony for the first time when he was twenty-one that he changed his mind and began to make sketches for his own first symphony. Fourteen years went by before he actually completed work on it in 1876, however, with the first performance given in the fall of that year with Brahms in the audience and a second some weeks later with the composer himself conducting.

Over the background sound of repeated pulsing beats from a kettledrum, the first movement (Un poco sostenuto) begins with a succession of vague murmurings in the orchestra that eventually take the form of the movement’s principal themes before bursting forth into the stormy first theme of the main section (Allegro) — an almost signature Brahms motif that rockets upward and remains briefly suspended before plunging downward again.

The slow second movement (Andante sostenuto) begins with a long, pensive lyric line that strengthens to a climax, with violins soaring as if to free themselves from the gravitational pull of the double basses at the bottom of the orchestral mix. Then, after a series of melancholic woodwind interludes and dramatic moments, the mood returns to the nostalgic sadness of the opening.

Brahms structured his third movement (Un poco allegretto e grazioso), a Beethoven-like scherzo, as a kind of instrumental song — a lyric outpouring colored by gentle woodwind sound.

The wonderful Finale (Adagio; Allegro non troppo, ma con brio), like a complete work in itself, opens with a rich and extensive introduction that begins with a darkly pensive hint at what will ultimately emerge as the movement’s principal theme. After that, like a distantly approaching storm, plucking sounds from the strings begin in the lower reaches of the orchestra and gradually increase in speed and intensity until the whole orchestra is involved in the tumult before a thunderous crash from drums ends the storm. What follows, as if to suggest the calm after the storm, is a gentle melody from a solo horn against a shimmering string background. The horn melody is then echoed by a flute before the extraordinary introduction concludes with a broad chorale for the brass section alone. The Finale’s main section begins with a rich, bold melody inspired, Brahms admitted, by the final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Both that theme and other secondary themes are then developed, but not in a traditional development “section,” until increasing tension erupts in an onrushing presto that is finally halted by a return to the noble brass chorale from the introduction in a strong fortissimo before the symphony moves on to a joyous conclusion. Program Notes by Courtenay Caublé

____________________

Robert Schumann – Symphony No. 2 in C major, Op. 61

Robert Schumann – Symphony No. 2 in C major, Op. 61

RSO, February 2016 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Petko Dimitrov, Guest Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Robert Schumann(1810-1856) – Symphony No. 2 in C major, Op. 61

- Sostenuto assai – Allegro ma non troppo

- Scherzo (Allegro vivace)

- Adagio espressivo

- Allegro molto vivace

Schumann’s Symphony No. 2 was composed from 1845–46. The first performance was November 5, 1846, in Leipzig with Felix Mendelssohn conducting the orchestra of the Leipzig Gewandhaus.

Toward the end of September, 1845, Robert Schumann wrote to his friend Felix Mendelssohn: “For several days drums and trumpets in the key of C have been sounding in my mind. I have no idea what will come of it.” Schumann did not wait long to find out. On December 12 of the same year, the diary he kept with his wife tells that he began composing a symphony, one in C major, with drums and trumpets playing conspicuous roles. Once embarked on a composition, Schumann often worked with great speed. In this case, it took only five days to draft the new symphony’s initial movement and less than two weeks for the remainder of the work. But having made this rapid start, the composer fretted over orchestrating his piano draft, this task ultimately costing him much of the ensuing year. He finally completed the Symphony No. 2 in October 1846, less than a month before its scheduled premiere. Shortly after its initial performance, several reviews extolled the symphony, and not just for its purely musical merits. More than one critic heard a lofty spiritual quality in the music, an aspiring toward almost religious expression. This is not entirely fanciful. Three of the symphony’s four movements use chorale-like melodies, and its signature theme seems nothing so much as a call from on high. There are, to be sure, no references to actual hymns, such as we find in Mendelssohn’s “Reformation” Symphony. But in its own abstract way, this symphony seems a kind of psalm, a song of praise and rejoicing.

Schumann begins the first movement with an introduction in moderate tempo. Its initial measures present two ideas set against each other in counterpoint: a flowing line for the strings and a solemn fanfare in the brass. The latter figure will prove a “motto” theme, one that recurs at important junctures throughout the symphony. (Listeners familiar with Haydn’s last symphony, the “London,” will note a resemblance between its opening fanfare and the one Schumann uses here.) Soon the music grows more active, its rhythms more animated, and the motto figure sounds again before the tempo accelerates into the Allegro that forms the main body of the movement. There, Schumann fashions his themes using the buoyant rhythms established in the latter part of the introduction, and he revisits the motto idea again during the accelerated coda that brings this first portion of the symphony to a close. The second movement seems an attempt to write a scherzo after Mendelssohn’s style, with light, running passagework in the violins. Yet the result is still distinctly Schumannesque, thanks chiefly to the restless harmonies the violin lines trace. Balancing this fleet music are two contrasting episodes, the second very like a hymn. The final statement of the scherzo music includes another recollection of the motto idea. Schumann builds the ensuing Adagio on a wide-stepping melody that seems more operatic than symphonic in character. This theme engenders the most beautiful slow movement among his orchestral compositions, a romance intimating deep poetic reverie. From the rocketing scale of its initial measure, the finale strikes a triumphal note, and Schumann maintains this for practically the full length of the movement. Eventually we hear recollections of the aria-like melody of the slow movement, as well as the motto theme.

What to Listen For: The symphony’s signature theme sounds in the opening moments: a stately fanfare played by the brass. It recurs late in the first movement, and in the second and fourth movements also. After the second movement’s scherzo comes one of Schumann’s most exquisite slow movements. Its principal theme first appears as a wide-stepping oboe solo, and Schumann recalls it briefly during the finale. Program notes Paul Schiavo, Seattle Symphony

____________________

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky – Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky – Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64

RSO, December 2017 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Eric Mahl, Guest Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) – Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64

- Andante-Allegro con anima – Molto più tranquillo

- Andante cantabile, con alcuna licenza – Non allegro – Andante maestoso con piano

- Valse. Allegro moderato

- Finale: Andante maestoso (E major) – Allegro vivace – Molto vivace – Moderato assai e molto maestoso – Presto

Ten years had passed since he had composed his fourth symphony, when, in the summer of 1888, a distressed Tchaikovsky wrote to his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck, telling her that he was afraid that he had lost his inspirational muse. He even quipped to her that, if he had to give up composing, he might just devote his time to raising flowers.

Desperately hopeful of overcoming his inspirational lapse, however, he forged ahead and began work on his fifth symphony. Composing the first movement proved to be difficult for him, but by the time he had finished the final movement, he was happily able to let Madame von Meck know that he seemed to have recovered and that things had turned out well.

Tchaikovsky himself conducted the first performance of his Symphony No. 5 in Saint Petersburg in November of 1888 and subsequently introduced it elsewhere in a European tour during which Brahms heard the work, pronouncing it excellent, “except for the finale”.

In the first movement (Andante – Allegro con anima), a clarinet darkly begins the long and slow introduction with a foreboding motto theme that will serve as a unifying element in the symphony. The first main theme then enters softly, building in intensity before the strings usher in a multi-element second theme that rises to lush lyricism in the violins. A brief development section is followed by a recapitulation, introduced by bassoons, and a dark coda that sets the mood for the second movement.

In the second movement (Andante cantabile, con alcuna licenza), after the lower strings intone a brief introduction, a solo horn sings a nostalgic main theme that soars in intensity as a second horn joins the first in a duet and a solo oboe and then a solo clarinet enter with additional melancholy lyricism to further enrich the emotionally warm mood.

The lyrically melancholy mood is suddenly shattered, however, by a fortissimo reappearance of the symphony’s opening motto theme. Then there is a pause, after which the movement’s earlier lyrical mood returns, as if in defensive protest, only to be challenged again by another fortissimo motto outcry. The battle between the two elements continues, with the movement ending in shattered phrases, the nostalgic mood defeated.

The third movement (Valse – Allegro moderato), a lilting waltz with a sort of chatty middle section, seems like a gentle reprieve until, in the coda, the Motto theme re-emerges like a distressing memory.

In the final movement (Andante maestoso – Allegro vivace – Molto vivace – Moderato assai e molto maestoso – Presto) the gloomy and even threatening motto theme, now in a major rather than a minor key, is wondrously transformed into a joyous song of triumph that dominates the rest of the symphony, happily intruding into the march-like second theme and leading it into a boisterous development section. Then, after a brief pause, the music rushes into a recapitulation in which the now happy motto theme merrily cavorts in a polyphonic environment before rushing the instrumental procession into a happily frolicsome coda in which Tchaikovsky has trumpets and horns toss the first movement’s first main theme about as a final unifying reminder. Program Notes by Courtenay Caublé

____________________

William Grant Still – Symphony No. 2 “Song of a New Race”

William Grant Still – Symphony No. 2 “Song of a New Race”

RSO, December 2019 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Yuga Cohler, Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

William Grant Still (1895-1978) – Symphony No. 2 in G minor

I – Slowly

II – Slowly and deeply expressive

III – Moderately fast

IV – Moderately slow

William Grant Still was born in Woodville, Mississippi, on May 11,1 895, and died in Los Angeles, California, on December 3, 1978. He was experienced in just about every aspect of music in American life, and his talents were such that he became a pathbreaker in all of them. The list of “firsts” that Still accomplished is astonishing. He was the first African-‐American composer to have a symphony performed by a major orchestra and an opera produced and televised by a major opera company (Troubled Island, produced by the New York City Opera in 1949). In 1936, Still became the first African-‐ American conductor to lead a major symphony orchestra (the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 1936), and he was also the first African-‐American conductor to conduct a radio studio orchestra (CBS Radio in New York in the ‘30s).

Still worked with great success in both “popular” and “classical” styles, creating musical scores for popular radio and television shows as well as large orchestral or choral pieces for the concert hall and full-‐scale operas for the stage, to say nothing of a voluminous body of chamber music. His commissions came from organizations as diverse as the League of Composers and the American Accordionists’ Association. Though he was always seen as a symbol for his race, he composed music that was universal in its appeal and approach. In recent years, new recordings of Still’s compositions as well as compact disc reissues of radio broadcasts from the 1930s and ‘40s, have made more of his music available—though still not half of his symphonies, and no more than a smidgen of music from his operas has been recorded. The inevitable reconsideration that comes at a composer’s centennial (which, for Still, occurred nearly 20 years ago) has begun—too slowly—to bring the welcome understanding that he was not simply a “niche” figure, not simply (as he was often styled in his lifetime) “the dean of African-‐ American composers,” but rather simply a great and unique American composer.

Still’s musical breadth came naturally from a wide range of experience of just about every kind of music imaginable. His parents were both music educators who were alert to signs of talent in their son. His father, a local bandmaster in Mississippi, died while the boy was still an infant; soon afterward, the family moved to Little Rock, Arkansas, where Still’s mother taught high school. His stepfather encouraged his musical talent by buying recordings of opera arias. After studies at Wilberforce College (which he left without completing a degree), Still worked for W.C. Handy in New York. Later he enrolled at Oberlin Conservatory, where he was encouraged to compose. He played the oboe in theater orchestras (including that for Sissle and Blake’s landmark show Shuffle Along) and studied composition in New York with Edgard Varèse. George Chadwick offered him a scholarship at the New England Conservatory and encouraged him to compose specifically American music (though in the end they only worked in private lessons).

It is hard to imagine any composer studying with two teachers as different as the avant-‐garde Italo-‐Franco-‐American Varèse and the staunch eighth-‐generation Yankee Chadwick. Yet it seems fair to say that if Still’s style more closely reflects Chadwick’s own romantic language, he certainly learned from his work with Varèse as well; but he found that the avant-‐garde style of Varèse was too different from the musical language of his people—the music of the blues and of spirituals which he wished to employ in serious concert work. It is perhaps safer to summarize Still’s style as “nationalist,” yet it drew from the technical and expressive devices learned both from his very diverse teachers and in the world he grew up in.

During much of his life Still worked as a gifted arranger for Handy, Paul Whiteman, and Artie Shaw. He conducted the CBS studio orchestra for the radio show “Deep River Hour” in New York, and he worked in Hollywood for films and television (including “Gunsmoke” and “Perry Mason”). He was a prolific composer in all musical forms, creating a total of five symphonies, nine operas, four ballets, and many other works. Biographical notes by Steven Ledbetter.

In the early 1920s, Still envisioned a trilogy of works depicting the African-American experience: the symphonic poem Africa representing their roots, the Symphony No. 1 ‘Afro-American’ (life in America to emancipation), and the Symphony No. 2 in G Minor ‘Song of a New Race’ (a vision of an integrated society). Still composed his second symphony in Los Angeles in 1936 and 1937. Leopold Stokowski led the Philadelphia Orchestra in the first performance on December 10, 1937 to rapturous reviews. Contemporary reviewers found it “of absorbing interest, unmistakably racial in thematic materials and rhythms, and triumphantly articulate in expressions of moods, ranging from the exuberance of jazz to brooding wistfulness.” Still’s typically luminous string writing is, throughout the work, very moving.

The first movement begins with an introduction with chiming celesta over string and wind (including cup-muted trumpets) presenting a pentatonic melody (pastoral in mood) leading to the woodwind introducing the main theme, which grows out of the introduction almost imperceptibly. Throughout the symphony at climactic moments, Still uses the brass to punctuate in the “call and response” fashion of the African-American church and the Negro spiritual. The movement builds to a proud, determined ending in the minor. The second movement’s main theme is distinctive and memorable as it glides up the G major scale to the leading tone (F#) with an air of nostalgia. In his orchestration in general, Still prefers to use the orchestral choirs (strings, woodwinds, brass, percussion) in alternation, much like his contemporary Roy Harris. So when solo instruments (oboe and violin) are used here, the effect is all the more telling. The middle section is much faster and animated before the main theme returns in all its lushness in the original tempo. Sudden rapid music interrupts a potential soft resolution of this movement, leading without a break into the third movement. This scherzo in cakewalk rhythm employs the “Scottish snap” rhythm which becomes a jazzy “doo-wa” inflection later when developed. The strutting, energetic rhythm reflects Still’s great skill in writing balletic music. Muted trumpets anticipate the main theme of the finale before the English horn introduces it in full. The music builds to an impressive, decisive peroration in g minor. The deep, non-aggressive but assertive, relentless drive throughout this movement (and much of Still’s music) may perhaps be a musical metaphor of the slow but inexorably steady progress of all Americans (but especially African-Americans) toward true racial freedom and equality. Program notes by David Ciucevich, Jr.

____________________

Johannes Brahms – Hungarian Dance No. 1

Johannes Brahms – Hungarian Dance No. 1

RSO, October 2016 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Barbara Yahr, Guest Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) – Hungarian Dance No. 1 in G minor

As a young pianist, Brahms met and for a while served as accompanist for the Hungarian violinist Eduard Reményi, who acquainted him with the traditional music of the Hungarian Roma (Gypsies). Enchanted by the music, Brahms later wrote four sets of Hungarian Dances, originally as piano duets just to entertain his friends at parties. But his friends were so delighted with them that they persuaded Brahms to publish them, the first four sets (which included No. 1 in G minor) appearing in 1869 and the remaining two in 1880. The public received them so well that he eventually wrote orchestral arrangements of Nos. 1, 3, and 10. Other composers have since orchestrated all of the others.

Most of the dances are fast and lively pieces, sonically reflecting the spirit of Hungarian folk melodies, with contrasting sections that enhance the overall musical effect. The energetic Hungarian Dance No. 1, marked Allegro molto, begins with a warmly surging main theme in the strings punctuated by chirping woodwind responses. Energetically playful and contrasting secondary dance themes follow before the warmly flowing main theme returns, only to be overruled by the more frolicsome material to bring the piece to a rousing conclusion.

Program Notes by Courtenay Caublé

____________________

Mikhail Glinka – Overture to Ruslan & Lyudmila

Mikhail Glinka – Overture to Ruslan & Lyudmila

RSO, May 2017 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Michael Lancaster, Guest Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Mikhail Glinka (1804-1857) – Overture to Ruslan & Lyudmila

More than a century after Mikhail Glinka’s death, Igor Stravinsky commented, with persuasive justification, that “all Russian music sprang from him.” The heritage of Russian folk music and Byzantine chant cannot be discounted, of course; but the distinctive character and colorful orchestration of Glinka’s music arguably led the way for such great composers as Rimski-Korsakov, Mussorgsky, and Tchaikovsky, who established a distinctive Russian musical identity in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Glinka chose the great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin’s most popular narrative poem, Ruslan and Lyudmila, as the story source for his second opera, which he composed in 1842. The fairy tale plot, set in Pagan Russia, tells the story of the lovely Lyudmila, the daughter of the Grand Duke of Kiev, who is desired by three suitors, one of them the heroic knight Ruslan, whom she chooses. Unfortunately, though, Ludmila is spirited away during their engagement party by evil spirits and delivered to the also evil dwarf Chernomor. Heroically overcoming various supernatural obstacles, Ruslan manages to reach his captured fiancée, but not before the wicked Chernomor has put her into a magical sleep. Ruslan takes her (still asleep) back to Kiev, where she is abducted once again, still asleep, by one of the rejected suitors. Ruslan hastens to the rescue yet again, though, and finding that the kidnapping suitor hasn’t been able to awaken her either, does so himself (with the aid of a magic ring), followed by rejoicing throughout the land.

One of the liveliest concert openers ever written, the Overture begins with forceful full-orchestra chords and dazzling scales that lead into two contrasting themes, both taken from the opera’s joyful final scene – the first an energetic march-like theme and the second the warmly passionate melody of an aria in which Ruslan praises the lovely Lyudmila.

After a development and recapitulation of the thematic material, there is a coda in which an ominous descending whole-tone scale played by trombones that recalls the evil Chernomor seems to undermine the happy mood before the overture ends in uncompromised rejoicing.

Program Notes by Courtenay Caublé

____________________

Ludwig van Beethoven – Symphony No. 3 in E flat Major “Eroica”

RSO, May 2017 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Michael Lancaster, Guest Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) – Symphony No. 3 in E-Flat Major, Op. 55

- Allegro con brio

- Marcia funebre – Adagio assai

- Allegro vivace

- Adagio molto

When Beethoven undertook the composition of his third symphony in 1803, his intention was to dedicate it to Napoleon Bonaparte, the French general who, in his opinion at the time, was a heroic champion of the French Revolution’s motivating values of freedom, liberty, and the pursuit of justice. He almost certainly thought of Napoleon as a sort of modern Prometheus, the Greek mythological hero who brought the tool of fire to mankind because of his concern for the welfare of the human race. When he learned, however, after having finished and dedicated the symphony to Napoleon, that his heroic champion had declared himself Emperor of France, his disgust was so consuming that he ripped away the title page of the original score, scratched out Napoleon’s name from the cover page of the conducting score, and renamed the work Sinfonia Eroica, Composed to Celebrate the Memory of a Great Man.

There were a few appreciative reviews of the symphony’s first public performance in April of 1805; understandably, though, there was considerable negative reaction from the general musical public, particularly for the work’s “excessive length” and for “obviously deliberate violations of the rules of form and style.” The reason, of course, was that it was unlike anything that anyone had ever heard before.

What is termed “absolute music” (music for its own sake, which can be funny or happy or sad, but which was not intended as an expression of the composer’s feelings or thoughts) was the standard for the “classical” period (Haydn’s age) in the second half of the eighteenth century; and, for the most part, composers rather stringently followed set rules of form and harmony.

Many regard Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony both as the first undisputed eruption of Beethoven’s maturing personal style and as the harbinger of a movement away from a “classical” approach in favor of a “romantic” one to musical composition – one in which the aforementioned rules and forms would remain as guidelines but could be modified or even violated in the service of a composer’s extra-musical purposes, such as the expression of personal feelings or the musical expression of an idea or vision.

Instead of a customary “classical” introduction, the symphony’s first movement (Allegro con brio) begins with just two loud staccato E-flat Major chords followed by the movement’s first theme – a strong one (perhaps derived from the main theme of Beethoven’s ballet The Creatures of Prometheus) that follows the pattern or an E-flat triad but which, instead of moving to a harmonically predictable destination, must have shocked that first audience by landing on a clashingly unrelated C sharp – a discord that Beethoven sustains with a crescendo – a trick deliberately intended to create an unresolved tension that he will maintain throughout the entire movement’s development, with each of the themes appearances violating harmonic predictability by moving toward an unresolved tension point. The astonishing development eventually explodes in a dissonant climax unlike anything that anyone in that audience could have ever heard. Then, towards the end of the movement, Beethoven surely must have shocked his first audience even more disturbingly with yet another trick. There is a soft violin tremolo on a pitch that seems obviously intended to lead to a restatement of the theme; but before it resolves into the expected key, a single French horn timidly starts to play the theme. The audience, of course, must have thought that the poor horn player had just carelessly come in too soon. It was no mistake, though. It was just Beethoven’s way of making sure that the tension created in that opening appearance of the main theme would remain unrelieved.

One usually thinks of funeral marches as gloomy music meant to represent or evoke tearful grief over the loss of a human life. The Eroica Symphony’s beautiful second movement (Marcia funebre: Adagio assai) isn’t that sort of piece, though. Instead, it is more of an evocation of heroic grief – a solemn but thoughtfully felt reminder of a life fully lived, one that has left a treasured legacy. A somber repeated rhythmic figuration, which remains throughout the movement as an undercurrent, is soon overlaid by an also somber but lyrical and noble theme that might best be described as a musical lamentation without tears for heroes who lived their lives in the service of justice and freedom.

The spirited movement that follows the noble funeral march (Scherzo: Allegro vivace) instantly dispels heroic grief, though, in favor of unalloyed joie de vivre. The scherzo is replete with fun, laughter and sunlight – a sort of grateful tribute to lives made secure and joyful thanks to the heroic deeds of others.

In the magnificent Finale (Allegro molto), rushing strings and exuberant chords lead fortissimo to the movement’s first thematic element, a thirteen-note line of widely separated notes played pizzicato and very softly by strings which Beethoven expands and develops with two variations before overlaying and combining it with the Prometheus theme borrowed from his earlier ballet, The Creatures of Prometheus. After that, the movement proceeds in theme-and-variations form, with eleven variations and a coda, which in effect is an additional variation, totaling twelve, each one of them uniquely enjoyable and impressive. The effect of the Finale as a whole, though, is overwhelming – a formidable conclusion for a masterpiece that many consider Beethoven’s finest work.

Program Notes by Courtenay Caublé

____________________

Joseph Haydn – Cello Concerto No. 1 in C major, Hob. VIIb/1RSO, March 2019 Concert, The Ridgefield Playhouse

Joseph Haydn – Cello Concerto No. 1 in C major, Hob. VIIb/1RSO, March 2019 Concert, The Ridgefield Playhouse

Yuga Cohler, Conductor

Jay Campbell, Cello

PROGRAM NOTES

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) – Cello Concerto No. 1 in C major, Hob. VIIb/1

- Moderato

- Adagio

- Allegro molto

Musicologists are sadly aware that there are works (including masterpieces) by great composers of the past that were not preserved and are hopelessly lost – a number of Johann Sebastian Bach’s cantatas for instance. Occasionally, though, to their surprise and joy, lost or previously unknown musical scores are unearthed. Specific ones that come to mind include numerous songs by Schubert and the incidental music that he wrote for the failed play Rosamunde, Johann Sebastian Bach’s keyboard masterpiece known as The Goldberg Variations, and Haydn’s Cello Concerto in C Major.

The Haydn Concerto was identified in 1961 in Prague’s National Library nearly 200 years after Haydn composed it, probably early in his forty-nine-year stay in the service of Prince Esterházy. The Czech government had confiscated the impressive collections of numerous noble families at the end of World War II, relocating them in the National Library, and musicologists have determined that the Haydn score had previously lain unappreciated in one of them for most of its nearly 200-year anonymity.

The Concerto’s twentieth-century premiere performance was given at the 1962 Prague Spring Festival, and the first performance for American audiences was given two years later in New York, with cellist Janos Starker as soloist.

Although undeniably “Classical” in its stylistic intent, residual elements from an earlier (“Baroque”) period are evident in the score. One can imagine, for instance, a very small orchestra of about fifteen or so players, with Haydn conducting while seated at a harpsichord, and with the solo cello very lightly accompanied and the full ensemble used only for introductions, endings, and in between solo spots. Except for attempts at an “authentic period” approach, of course, modern performances can bypass efforts at period authenticity in favor of enhancing the music’s impact for present-day audiences.

The first movement (Moderato) begins with first violins and a solo oboe singing a trippingly jaunty theme that will skip along merrily throughout the entire movement, including the development and recapitulation, without challenging contrast from a second theme; and once the solo cello enters, happily joining the merriment, Haydn has it hold our attention unchallenged right through a virtuoso cadenza display at the movement’s conclusion.

Haydn begins the slow second movement (Adagio) by having the solo cello enter softly and expressively with a long, sustained note beneath the sound of the strings as they continue to play before the solo cello’s sustained note blossoms into a rich development of the thematic material. There is a middle section with an even deeper thematic flavor that urges a correspondingly greater expressive richness from the solo cello and a shortened return to the opening material before the movement ends with a second cadenza.

The lighthearted finale (Allegro molto) opens with a very short thematic fragment played by fist violins and an oboe that becomes a basic element of the movement. The solo cello enters in the same way as in the slow movement, with a long, sustained note, but one that ends this time in an upward-rushing scale to join the orchestra in a frenetic romp that flavors the rest of the movement. Rather than as a contrasting element, Haydn obviously composed the movement’s central segment mainly as a display ground for the soloist’s virtuosity; and the same intent seems obvious for the rest of the movement as well, all the way to an exuberant close that Haydn must surely have hoped would leave listeners both smiling and in awe of a soloist’s mastery. From a present-day point of view, of course, it should also leave listeners very happy that Haydn’s Concerto didn’t remain lost.

Program Notes by Courtenay Caublé

____________________

Johannes Brahms – Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73

Johannes Brahms – Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73

RSO, December 2018 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Yuga Cohler, Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Johannes Brahms (1933-1897) – Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73

- Allegro non troppo

- Adagio non troppo

- Allegretto grazioso

- Allegro con spirito

Brahms composed his Second Symphony in the summer of 1877; Hans Richter conducted the first performance in Vienna on December 30, 1877. Within months after the long-awaited premiere of his First Symphony, Brahms produced another one. The two were as different as night and day—logically enough, since the first had taken two decades of struggle and soul-searching and the second was written over a summer holiday. If it truly was Beethoven’s symphonic achievement that stood in Brahms’s way for all those years, but nothing seems to have stopped the flow of this new symphony in D major. Brahms had put his fears and worries behind him.

This music was composed at the picture-postcard village of Portschach, on the Worthersee, where Brahms had rented two tiny rooms for his summer holiday. The rooms apparently were ideal for composition, even though the hallway was so narrow that Brahms’s piano couldn’t be moved up the stairs. “It is delightful here,” Brahms wrote to Fritz Simrock, his publisher, soon after arriving, and the new symphony bears witness to his apparent delight. Later that summer, when Brahms’s friend Theodore Billroth, an amateur musician, played through the score for the first time, he wrote to the composer at once: “It is all rippling streams, blue sky, sunshine, and cool green shadows. How beautiful it must be at Portschach.” Eventually listeners began to call this Brahms’s Pastoral Symphony, again raising the comparison with Beethoven. But if Brahms’s Second Symphony has a true companion, it is the violin concerto he would write the following summer in Portschach—cut from the same D-major cloth and reflecting the mood and even some of the thematic material of the symphony.

When Brahms sent the first movement of his new symphony off to Clara Schumann, she predicted that this music would fare better with the public than the tough and stormy First, and she was right. The first performance, on December 30, 1877, in Vienna under Hans Richter, was a triumph, and the third movement had to be repeated. When Brahms conducted the second performance, in Leipzig just after the beginning of the new year, the audience was again enthusiastic. But Brahms’s real moment of glory came late in the summer of 1878, when his new symphony was a great success in his native Hamburg, where he had twice failed to win a coveted musical post. Still, it would be another decade before the Honorary Freedom of Hamburg—the city’s highest honor—was given to him, and Brahms remained ambivalent about his birthplace for the rest of his life.

In the meantime, the D major symphony found receptive listeners nearly everywhere it was played. From the opening bars of the Allegro non troppo—with their bucolic horn calls and woodwind chords—we prepare for the radiant sunlight and pure skies that Billroth promised. And, with one soaring phrase from the first violins, Brahms’s great pastoral scene unfolds before us. Although another of Billroth’s letters to the composer suggests that “a happy, cheerful mood permeates the whole work,” Brahms knows that even a sunny day contains moments of darkness and doubt—moments when pastoral serenity threatens to turn tragic. It’s that underlying tension—even drama—that gives this music its remarkable character. A few details stand out: two particularly bracing passages for the three trombones in the development section, and much later, just before the coda, a wavering horn call that emerges, serene and magical. This is followed, as if it were the most logical thing in the world, by a jolly bit of dance-hall waltzing before the music flickers and dies. Eduard Hanslick, one of Brahms’s champions, thought the Adagio “more conspicuous for the development of the themes than for the worth of the themes themselves.” Hanslick wasn’t the first critic to be wrong—this movement has very little to do with development as we know it—although it’s unlike him to be so far off the mark when dealing with music by Brahms. Hanslick did notice that the third movement has the relaxed character of a serenade. It is, for all its initial grace and charm, a serenade of some complexity, with two frolicsome presto passages (smartly disguising the main theme) and a wealth of shifting accents. The finale is jubilant and electrifying; the clouds seem to disappear after the hushed opening bars, and the music blazes forward, almost unchecked, to the very end. For all Brahms’s concern about measuring up to Beethoven, he seldom mentioned his admiration for Haydn and his ineffable high spirits, but that’s who Brahms most resembles here. There is, of course, the great orchestral roar of triumph that always suggests Beethoven. But many moments are pure Brahms, like the ecstatic clarinet solo that rises above the bustle only minutes into the movement, or the warm and striding theme in the strings that immediately follows. The extraordinary brilliance of the final bars—as unbridled an outburst as any in Brahms—was not lost on his great admirer Antonín Dvorák when he wrote his Carnival Overture.

Program notes by Phillip Huscher of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

____________________

Robert Schumann – Symphony No. 1 in B♭ major, Op. 38 (Spring)

Robert Schumann – Symphony No. 1 in B♭ major, Op. 38 (Spring)

RSO, May 2019 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Yuga Cohler, Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) – Symphony No. 1 in B♭ major, Op. 38 (Spring)

- Andante un poco maestoso – Allegro molto vivace

- Larghetto

- Scherzo: Molto vivace – Molto piu vivace

- Allegro animato e grazioso

Robert Schumann undertook the composition of symphonies in a determined attempt to conquer the most highly regarded of all musical forms. Throughout the 1830s he had turned more and more to composition as a hand injury put an end to his hopes for a career as a virtuoso pianist. His first departure from an almost exclusive concentration on piano music came in 1840, when the joyous prospect of finally being able to marry his beloved Clara Wieck (over her father’s determined opposition) motivated an extraordinary outpouring of songs, among them three of his four principal song cycles, written in feverish energy during May and June. That September, Robert and Clara were married in a village church near Leipzig.

By the beginning of 1841, their union was proving fruitful in two ways: Clara was already pregnant with Marie, the first of their eight children, and Robert demonstrated his own fecundity with a new burst of music—only now, with Clara’s encouragement, he wanted to compose in the largest, the most demanding musical forms. So caught up was he in the ceaseless eruption of new music that his bride began to feel a little alarmed about the non-stop composing and somewhat neglected.

If 1840 had been the “song year,” 1841 was a “symphony year.” Though Schumann had composed most of a symphony in G minor in 1832, and had even heard a performance of the first movement, he had ultimately left the work unfinished. When he was finally ready to bring forth a symphony, the music virtually poured out of him. He sketched the entire piece in just four days, from January 23 to 26! He completed the orchestration by February 20 and heard a performance under Mendelssohn’s direction on March 28.

Much encouraged by the audience’s approval, Schumann worked on further “orchestral plans.” First came what he called his “symphonette”—the Overture, Scherzo, and Finale in E composed between April 12 and May 8. It was followed at once by a “Fantasie in A minor” for piano and orchestra that we now know as the first movement of the Piano Concerto, completed by May 20. Ten days later he began a new Symphony in D minor, at first referred to as his second, though it was finally published—and is known today—as the Fourth. This he completed by September and followed at once with a never-finished symphony in C minor. Thus, in less than a year, Schumann wrote the better part of four symphonies and a good chunk of the Piano Concerto!

Both the completed symphonies underwent a certain amount of retouching. In the case of the First, the revisions were relatively slight. But for the D minor Symphony, the changes were more far-reaching and kept the work from publication for a decade, by which time Schumann had finished and published his other two contributions to the genre.

Schumann’s First Symphony burgeons with new life. He himself thought of it from the outset as a “Spring Symphony” and even gave characteristic titles to the four movements, though in the end he suppressed them in order to avoid creating critical assertions that his Symphony was simply a work of scene-painting. A spring poem by Schumann’s friend Adolph Böttger may have played a major role in inspiring the work. Certainly the opening fanfare in the trumpets and horns can be heard as a setting of the poem’s last line, “Im Thale blüht der Frühling auf!” (In the valley, spring blossoms forth!), and that fanfare creates the basic shape of the principal Allegro theme that follows after the stormy introduction yields to spring, and continues to play an important role through much of the movement. The opening motive dominates through the development with impetuous energy, while the fragrant secondary theme, first heard in the woodwinds over rustling commentary in the strings, offers welcome contrast. The development culminates in a magnificent peroration for the full orchestra of the opening motto, now drawn out at length. Following the recapitulation, Schumann brings in a new, soaring melody of great lyricism.

The slow movement usually brings out the most expressive side of Schumann. Here it appears in a broad instrumental melody colored by a striking harmonic plan. The movement does not come to a formal ending, but leads right into the fiery Scherzo, which has some of the energy of Beethoven. The finale bursts forth impetuously in a striking rhythm that contrasts with more dancelike material to bring the work to a rousing close.

Program notes by Steven Ledbetter

____________________

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov – Scheherazade, Op. 35

RSO, October 2017 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Yuga Cohler, Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) – Scheherazade, Op. 35

- The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship

(Largo e maestoso — Lento — Allegro non troppo — Tranquillo) - The Kalendar Prince

(Lento — Andantino — Allegro molto — Vivace scherzando — Moderato assai — Allegro molto ed animato) - The Young Prince and The Young Princess

(Andantino quasi allegretto — Pochissimo più mosso — Come prima — Pochissimo più animato) - Festival At Baghdad. The Sea. The Ship Breaks against a Cliff Surmounted by a Bronze Horseman.

(Allegro molto — Lento — Vivo — Allegro non troppo e maestoso — Tempo come I)

Although inspired by Arabian stories, Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade is entirely Russian in its “oriental” overtones. Held together by the lovely Scheherazade theme played by a solo violin that introduces each segment, the work’s semi-programmatic structure is based on the story of Scheherazade herself.

According to the well-known story, the Sultan Shariyar, who had been betrayed by his first wife, had had her executed and had vowed to marry a new wife every day thereafter and then execute her after their wedding night. After hundreds of hapless young girls had consequently lost their heads during the ensuing three years, the clever girl Scheherazade, the Sultan’s Grand Vizier’s daughter, armed with a clever survival plan, persuaded her father to propose her as the Sultan’s next wife. Her plan, which she immediately put into action, was to have her sister spend the wedding night in the apartment with the royal couple and in the morning ask Scheherazade to tell her a story. Scheherazade, with the Sultan also listening, was to do so, stopping before the end of the story and promising to reveal the ending the next night.

Rimsky-Korsakov commented that he did not intend to follow direct depictions of Scheherazade’s stories, but only “to slightly lead a listener’s imagination along the path that [his] fancy travelled”. The first segment, The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship, introduces two contrasting themes. The first, a rather severe one heavily colored by brass instrumentation, suggests the uncompromising Sultan, and the second, a gracefully flowing violin song introduced by woodwinds, calls to mind the innocent Scheherazade. Rimsky himself described the two themes, pointing out that they are “purely musical material” and that they recur repeatedly throughout the entire work, each time under different moods and “corresponding each time to different images, actions, and pictures.” In the first movement the two themes weave along over a rocking third melody that suggests the ocean’s waves.

The main theme of The Tale of the Kalendar Prince (a prince who pretends to be a member of a tribe of wandering dervishes called Kalendars) is an oriental-sounding melody played sequentially by the full orchestra and a variety of solo instruments. Brass instruments introduce a second theme – a brisk march -that is interrupted by a lovely clarinet solo that calls to mind the whirling movements of the dervishes.

Lyrically romantic tunes colored by the sound of woodwinds, harp, and higher against lower strings weave contrapuntally through The Young Prince and the Young Princess, with the segment ending in quick figurations that seemingly dance away into the distance.

The lovely violin melody that represents Scheherazade introduces the final movement, which begins with an energetic dance theme enlivened by the sound of tambourine and cymbals that suggests The Festival at Baghdad. The dance becomes even more animated, with added punctuation from snare and bass drums before a brass fanfare leads into a reprise of some of the work’s earlier themes. The sound of the rise and fall of sea waves in the first movement is recalled until, with a crashing chord, The Ship Goes to Pieces on a Rock Surmounted by a Bronze Warrior. Then a sweeping return of the Sultan’s theme, also from the first movement, quietens, suggesting Shariyar’s mollified intentions, and the beautiful violin theme that represents the lovely Scheherazade returns to end her tale with a sequence of quiet harmonics over a broadly sustained chord.

Program notes by Courtenay Caublé

____________________

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551 (Jupiter)

RSO, March 2018 Concert, The Ridgefield Playhouse

John Cuk, Guest Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) – Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551 (Jupiter)

- Allegro vivace

- Andante cantabile

- Allegretto Molto allegro

Mozart’s Symphony in C major, K. 551, was the last of three symphonies its author wrote with remarkable speed during the summer of 1788. The origin of this symphonic trilogy — to which the Symphony in E-flat, K. 543, and the famous G-minor Symphony, K. 550, also belong — has been the subject of much debate and speculation among Mozart scholars. It was unusual for the composer to create substantial works without a commission or at least the prospect of a performance, yet no occasion for the presentation of these symphonies is known to have existed. Although several theories have been proposed, we cannot say with certainty why Mozart composed these works. The sobriquet “Jupiter,” by which this work has long been known, did not originate with Mozart but, apparently, with an English publisher in the early 19th century. It seems, however, quite appropriate to the Olympian breadth and majesty of the piece.

The work’s opening exemplifies the expressive duality that so thoroughly informs Mozart’s music and, apparently, reflected something fundamental in his character. The long initial subject begins with brief two-part phrases that start vigorously but turn almost at once pliant and gracious. A second theme offers a similarly complex character. Yet it is the light-hearted and apparently innocuous third melody to which Mozart first turns his attention in the movement’s central “development” section, using its final measure as the subject of a bold contrapuntal passage. After the exhilarating energy of the opening movement, the second offers music that the eminent Mozart scholar Alfred Einstein called “a broad and deep outpouring of the soul.” Then follows a splendid and inventive minuet, enlivened by a skilled yet unobtrusive use of counterpoint. But it is in the finale that Mozart’s genius for contrapuntal writing fully reveals itself. The famous opening subject gives rise to a succession of subsidiary ideas, which Mozart interweaves in various ways. The closing section of the movement offers a breathtaking integration of thematic material.

Program notes by Seattle Symphony

____________________

Antonin Dvořák – Symphony No. 9, Op. 95 (From the New World)

RSO, October 2019 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Yuga Cohler, Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

Antonin Dvořák (1841-1904) – Symphony No. 9, Op. 95 (From the New World)

- Adagio – Allegro molto

- Largo

- Scherzo: Molto vivace

- Allegro con fuoco

In 1892 Dvořák accepted an invitation to serve as Director of the National Conservatory of Music in New York. His stay in the United States, which included one summer in the Czech colony in Spillville, Iowa, ended after only three years, when homesickness for his beloved Bohemia won out over enthusiastic efforts to urge him to remain.

Powerfully influenced in his compositions by the folk music of his native land, Dvořák found himself equally attracted especially to American Negro folk music. Ironically, the famous theme in the slow movement of his Ninth Symphony (“From the New World”), which has become well-known around the world as “Goin’ Home,” is frequently misconstrued as a famous Negro spiritual, although it is really an entirely original Dvořák melody. In a letter to a German conductor, Dvořák commented, “Omit that nonsense in your program notes about my having made use of Indian and American motives. I tried only to write in the spirit of those national American melodies.” Above all, Dvořák wanted to give musical voice to his impressions of what he saw as a young and growing country, and in truth there is at least as much of the Czech spirit and of the composer’s own personality in the score as there is of anything essentially “American.”

The first movement (Adagio – Allegro molto) is built on three themes. After a slow introduction, an arpeggio-like, energetic first theme is answered by a phrase with a dotted-note rhythm that persists in the bridge passage leading to the second theme, a folk-like melody more Bohemian than American in character, introduced by flute and oboe. A third theme, first played by a solo flute, is another folk-like melody, this time actually based on Dvořák’s favorite Negro spiritual, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” The wonderful development section elaborately treats the first and third themes, unified by the aforementioned dotted figuration and made aurally exciting by frequent crescendos and diminuendos and shifts back and forth between high and low registers. Then, after a recapitulation of the thematic material, the movement ends in a majestic coda and a fortissimo return to the arpeggio segment of the opening theme.

The famous second movement (Largo) opens with quiet, distant chords out of which emerges the voice of the solo English horn singing the “Goin’ Home” theme. The darkly colored middle section of the movement’s ABA form, in fine contrast to the end sections, concludes with a unifying reminder of the arpeggio motif from the first movement.

The Scherzo (Molto vivace) begins with a highly rhythmic dance tune much more Czech than American in character that is followed by a charming folk-song-like contrasting theme introduced by flute and oboe. The three-part movement, which contains a number of unifying echoes of material from the first movement, ends with a return to the dance-like opening theme.

The sonata-form Finale (Allegro con fuoco) opens with a fierce introduction that leads to a march-like first theme played by trumpets and horns. The second theme, in marked contrast to the first, is a limpidly lyrical one sung by a solo clarinet, and the third is a sort of song ending with a three-note figure reminiscent of “Three Blind Mice” with which Dvořák has fun as he tosses it around among various orchestral voices. The development makes much use of earlier thematic material, and the symphony ends with grandiose enthusiasm.

Program Notes by Courtenay Caublé

____________________

Edward Elgar – Cello Concerto in E Minor, Op. 85

Edward Elgar – Cello Concerto in E Minor, Op. 85

RSO, October 2017 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Yuga Cohler, Conductor

Julian Schwarz, Cello

PROGRAM NOTES

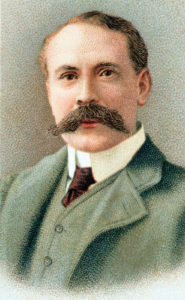

Edward Elgar (1857-1934) – Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85

- Adagio – Moderato

- Lento – Allegro molto

- Adagio

- Allegro – Moderato – Allegro, ma non-troppo – Poco più lento – Adagio

The Elgar Cello Concerto is a glorious work that suffered the misfortune of a catastrophic first performance in 1919, when the poorly rehearsed orchestra gave it such a wretched showing that critics gave it mercilessly negative reviews. Fortunately, subsequent performances and judgments have righted the wrong. Unlike most of Elgar’s other works, which are generally cheerful or noble in style, the Cello Concerto is introspective in its mood, reflecting the despair and disillusionment that Elgar felt at the end of World War I, the so-called “War to End All Wars,” with all its death and destruction.

The first movement (Adagio -Moderoto) begins with a dramatic recitative and a brief cadenza for the solo instrument. The violas then sing the first theme, which is repeated and broadened into a more moving statement by the solo cello. The orchestra then restates the theme once more before moving to a more gently lyrical second theme before returning to the main theme, this time presented as a sort of remote, distant echo of its original nature. Without a break, the first movement moves into the lively and more lighthearted second movement (Lento -Allegro mo/to), which is very much like a scherzo in effect, though not in meter. The third movement (Adagio) both begins and ends with a quietly lyrical melody -a theme that dominates the entire movement, imbuing it with a sweetly nostalgic mood. Then, with a sudden shift from major to minor tonality, there is a telling mood change as the Finale begins, once again without a pause between movements. Undergoing frequent changes in tonality, the main theme of the fourth movement seems restless, with somber undertones that lend it a nearly menacing quality. As the movement nears its conclusion, new themes are introduced at a slower tempo that becomes even slower until the musical flow stops entirely on a held chord. Then, as the concerto moves towards its closing measures, the beginning of the first movement is revisited with subtle alterations before the fourth movement’s main theme returns, moving with mounting tension to three final chords.

Program Notes by Courtenay Caublé

____________________

César Frank – Symphony in D Minor

RSO, May 2018, Richardson Auditorium

Yuga Cohler, Conductor

PROGRAM NOTES

César Franck (1822-1890) – Symphony in D Minor

1. Lento; Allegro ma non troppo

2. Allegretto

3. Allegro non troppo

César Franck’s beautiful D minor Symphony was harshly criticized by both critics and other composers after its premiere at the Paris Conservatory in 1889, even insultingly by the great Charles Gounod as well as absurdly by one pompous (and ill-informed) critic who maintained that the work couldn’t possibly qualify as a symphony because Franck had used an English horn in it. Sadly, Franck died only a few months afterwards, never finding out that his symphony would eventually become an audience favorite, better loved and more highly regarded than most of even Gounod’s music.

The Symphony has three movements, with the middle movement serving as both an adagio and a scherzo. The first movement (Lento; Allegro ma non troppo) begins with a slow introductory section in which the lower strings introduce a three-note motto theme that has been a favorite of several major composers who have thought of it as the musical posing of an ominous question. Beethoven used it in one of his last string quartets, writing the questioning words “Muss es sein” (“Must it be?) over the three notes. Wagner used it in his Ring of the Nibelungen as the questioning Leitmotiv (identifying theme) of Fate, and Franz Liszt used it as the main theme of his symphonic poem Les Préludes. The questioning phrase is then repeated several times, each time with increasing intensity as the music builds towards the movement’s main section, an Allegro in sonata form in which the motto is transformed into an aggressively energetic main theme. A turbulent development then builds until suddenly the intense yearning explodes into a soaring melody, with the rest of the movement filled with conflict between the two moods until the question posed by the motto theme is finally answered in passionate affirmation.

The second movement (Allegretto) begins with softly plucked sounds from the harp and strings over which an English horn soon begins to intone a beautiful but wistfully melancholy song. The movement’s gay and carefree middle section provides a contrasting emotional gleam of light.

Like the final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Franck’s finale (Allegro non troppo) is an example of “cyclic” structuring. The movement is essentially festive in mood, with a gorgeous opening theme and other thematic richness; but there are revisitings of the questioning and melancholy moods of the earlier movements. Franck causes them to move, however, towards mounting affirmation and strength, with the melancholy theme from the second movement reshaped into a joyful song and all the gloomy questionings triumphantly resolved.

Program Notes by Courtenay Caublé

____________________

Ludwig van Beethoven – Symphony No. 1 in C Major, Op. 21

RSO, October 2018 Concert, Richardson Auditorium

Yuga Cohler, Conductor

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) – Symphony No. 1, in C Major, Op. 21

- Adagio molto – Allegro con brio

- Andante cantabile con moto

- Menuetto: Allegro molto e vivace – Trio

- Finale: Adagio – Allegro molto e vivace

With his First Symphony, Beethoven staked his claim as a rightful heir to the Classical symphonic tradition. After its premiere, at a typically gargantuan benefit concert in Vienna’s Burgtheater on 2 April 1800, the critic of the influential Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung wrote of the work’s ‘considerable art, novelty and wealth of ideas’, adding that its only flaw was ‘the excessive use of wind instruments, so that there was more Harmonie [wind-band] than orchestral music as a whole’. He also complained of the poor quality of performance, especially in the slow movement, where rhythm and ensemble became sloppy. Unconfirmed reports suggest that other listeners were fazed by the off-key opening. But, unlike some of Beethoven’s radical early piano sonatas, the First Symphony, in the ceremonial, trumpet-and-drum key of C major, contained little to alarm an audience who by 1800 had absorbed the challenges of Haydn’s and Mozart’s late symphonies.

The young Beethoven had produced a stream of brilliant compositions for the piano during the 1790s. But he was understandably far more circumspect when it came to the string quartet and the symphony, the two most elevated Classical genres, and the ones in which Haydn, still at the height of his powers, especially excelled. Beethoven began to sketch a symphony in C major in 1795–6, then abandoned it when he struck an impasse with the finale. Some time in the autumn of 1799, while he was grappling with the Op. 18 String Quartets, he re-used part of the jettisoned first movement as the finale of a new symphony, and composed the other three movements from scratch.

The First Symphony’s notoriously oblique beginning, with wind and pizzicato strings – a novel and striking colouring – proposing first F major, then G major (not the expected ‘home’ key of C major), has in fact even more daring precedents in the music of C. P. E. Bach. But Beethoven sustains the air of expectancy by continually avoiding the chord of C major in its strongest (‘root’) position; and there is an exhilarating sense of release when the introduction propels itself without a pause into the crisp, martial theme of the Allegro con brio. This speaks the language of the Classical comedy of manners as perfected by Haydn and Mozart, albeit slightly roughened by the young composer’s trademark trenchancy and the urgency of his musical argument. It is also more densely scored than anything in Haydn’s and Mozart’s symphonies, with the winds and strings often used in antiphonal blocks. Throughout the movement Beethoven makes inspired play with the three elements of the main theme: a descending scale flourish, peremptory dotted figures and an upwardly striding arpeggio. Boisterous conviviality is briefly threatened when the second theme – a graceful dialogue between flute and oboe underpinned by the first theme’s rising arpeggio – darkens mysteriously into the minor key in cellos and basses against a plangent oboe descant. The triumphant fortissimo recapitulation of the main theme is a characteristic Beethoven ploy, as is the flamboyant coda that resolves the movement’s harmonic tensions by distilling the main theme into its most elemental form.For his first symphonic slow movement, Beethoven eschews the ruminative depths he had plumbed in the adagios of several early sonatas and chamber works and writes a graceful, pawky F major Andante cantabile con moto that initially pretends to be a fugue. (The musicologist Donald Francis Tovey and others have pointed out the music’s kinship with the playful, fugally inclined Andante of Beethoven’s contemporary C minor String Quartet, Op. 18 No. 4.) At the start of the recapitulation Beethoven delightfully enriches the fugal weave with a skittish new counter-melody. The solemn pianissimo drum rhythms that underpin the closing theme become more assertive in the development, which slews round into the rich and remote-sounding key of D flat major.

Although Beethoven dubbed the third movement ‘Menuetto’ – either from convention, or with his tongue in his cheek – what he wrote was a scherzo of coursing energy and explosive dynamic contrasts, a natural consequence of Haydn’s rude shake-up of the traditional minuet in his ‘Surprise’ Symphony and the first and last of his Op. 76 String Quartets. In the second half Beethoven wrenches the music into D flat major (shades here of the second movement) before returning to the home key via a hushed, tense sequence of modulations.

From its tiny, stuttering introduction – the kind of ‘blurt-it-out-then’ joke Haydn liked to reserve for his codas – to the unscheduled last-minute entrance of a march for toy soldiers, the Finale is one of Beethoven’s most teasingly amusing creations. His main agent of comic suspense and subversion is the rising scale which the violins initially have such difficulty completing. In the development this propels the music to the surprise key of B flat for a bout of mock-heroics, before being turned upside down in a jousting match for first and second violins. Then, just as the woodwind are engineering a poised, Mozartian lead back to the recapitulation, the irrepressible agent provocateur scampers in before we realize it, with a gleeful irreverence.

Program notes © Richard Wigmore