Finlandia, Op. 26 – Jean Sibelius

BORN: December 8, 1865. Tavestehus, Finland

DIED: September 20, 1957. Järvenpää, Finland

COMPOSED/WORLD PREMIERE: Sibelius composed Finlandia in 1899 for performance at a political demonstration held in Helsinki on December 14 of that year. He revised it in 1900

INSTRUMENTATION: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones and tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, and strings

THE BACKSTORY: In the 1890s, Sibelius was recognized by Finland as its greatest composer. After 1900, he became famous around the world. Finlandia marked the turning point. Its popularity surprised no one more than Sibelius, who had agreed to contribute some music to a public demonstration in Helsinki. But 1899 was a time of heightened political tensions, as the Russian hold on Finland was growing tighter, and so a simple and brief, but stirring composition called Finland Awakes, crowned by a big singable tune, struck home like a thunderbolt. The following year, Sibelius revised the score and gave it the title Finlandia. The Helsinki Philharmonic, then only eighteen months old, took the music on its first major tour, carrying Sibelius’s name throughout Europe (the tour ended at the Paris World Exposition). Despite the narrow political circumstances of its creation, Finlandia turned out to have universal appeal, and it soon made Sibelius the best-known living Finn.

THE MUSIC: Just a few minutes in length, this piece inspired national pride and brought Sibelius personal fame and sweeping popularity. Just as Boléro eventually hounded Ravel, the success of Finlandia came to irritate Sibelius, particularly when it overshadowed greater and more substantial works. Still, this is highly effective music, richly scored and imaginatively colored—those dark clouds at the top are particularly unforgettable. Best of all, it boasts one of music’s great melodies, although, as in Elgar’s most famous Pomp and Circumstance march, it sometimes catches audiences by surprise, coming at the very last minute. – Program Notes by Phillip Huscher

—–

Vier letzte Lieder (Four Last Songs) – Richard Strauss

BORN: June 11, 1864. Munich, Kingdom of Bavaria, German Confederation

DIED: September 8, 1949. Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Bavaria, West Germany

COMPOSED: 1957

WORLD PREMIERE: London on May 22, 1950. The premiere was given posthumously at the Royal Albert Hall in London, sung by Kristen Flagstad, accompanied by the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler.

INSTRUMENTATION: 2 flutes and piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets and high clarinet in E-flat, 2 bassoons and contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, snare drum, triangle, cymbals, bass drum, tam-tam, bells, xylophone, 2 harps, piano, celesta, and strings

THE BACKSTORY: Strauss composed his beautiful Four Last Songs in 1947, just a year before his death. Both the poetry and the music to which the poetry is set reflect Strauss’s mediation on life, death and the soul’s transition into “the magic circle of the night” and his serene acceptance of the inevitability of this own death. Two years earlier, in 1946, Strauss had been inspired buy Joseph Eichendorff’s poem IM Abendrot (In the Glow of Evening) to compose a song that might prepare him for death; and soon thereafter a friends’ gift to him of a collection of Heinrich Heine’s poems motivated him to write four additional songs for a collection of five that would address different aspects of the same subject. He was able to compose music for only three of the songs based on Heine’s poetry before he died, and he never heard the songs performed.

A “lied” is a poem set to music and sung, usually with piano accompaniment. Other composers have written Lieder with orchestral accompaniment, but Strauss’s expertise at orchestration in conjunction with voice and poetry is very special in its contribution to the emotional effect of the whole. Also, Strauss uses the soprano voice, which was his favorite above all others, in a way that make the vocal line meld into the orchestral fabric.

As afterthought: In the song Im Abendrot, Strauss quotes the “transfiguration” theme from his tone poem Tod und Verklarung (Death and Transfiguration), which he had composed many years earlier, shortly afterward explaining to a friend that “transfiguration” meant that “as the hour of death approaches, the soul leaves the body in order to find gloriously achieved in everlasting space those things which could not be fulfilled here below.” Moments before he died, Strauss told those by his bedside: “Death is just as I envisioned it in Tod und Verklarung.” – Program Notes by Courtney Cauble

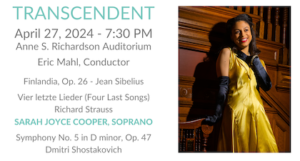

Sarah Joyce Cooper, Soprano

Sarah Joyce Cooper has received praise for her “meltingly beautiful” (Opera News) singing and “passionate power” (Parterre Box). Performances this season include a return to Carnegie Hall as the soloist in a performance of John Rutter’s Magnificat and Stephen Schwartz’s When You Believe, an appearance with the Boston Youth Symphony Orchestra as Clotilde in a semi-staged production of Bellini’s Norma, and a debut with the Ridgefield Symphony Orchestra as the soloist in Strauss’s Vier letzte Lieder. As an Emerging Artist with Boston Lyric Opera, Ms. Cooper will appear in mainstage performances of Joseph Bologne’s The Anonymous Lover as a chorus member, covering the role of Jeannette. Ms. Cooper also looks forward to making her debut with Seattle Opera as Minnie Tate in Tazewell Thompson’s Jubilee in October 2024.

Recent concert performances include her Carnegie Hall debut as the soloist in Poulenc’s Gloria with the New England Symphonic Ensemble, the roles of Eva and Gabriel in Haydn’s Creation with the MIT Concert Choir and Handel and Haydn Society Chamber Choir, and soloist with the Eastern Connecticut Symphony Orchestra in Brahms’ Ein Deutches Requiem. Operatic credits include Adina in L’Elisir d’amore (Geneva Light Opera), Clorinda in La Cenerentola (Syracuse Opera), La Charmeuse in Thaïs (Maryland Lyric Opera), Juliette in Roméo et Juliette (Opera Western Reserve), Violetta in La Traviata (MassOpera), Mimì in La Bohème (Opera Theater of Cape Cod/ Boston Opera Collaborative), Micaëla in Carmen (Prelude to Performance), Zerlina in Don Giovanni (Boston Opera Collaborative), Pamina in Die Zauberflöte, and Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro (Savannah Voice Festival). Ms. Cooper has also appeared as a soloist with the Boston Youth Symphony Orchestra, the Rochester Oratorio Society, and the Harvard Radcliffe Chorus. In 2019, she was invited to perform as a soloist with the Du Bois Orchestra in the historic world premiere of Florence Price’s long-lost cantata, Abraham Lincoln Walks at Midnight.

As a competition winner, Ms. Cooper has received awards from the George London Foundation and Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions and was nominated for a study grant from the Sarah Tucker Foundation. She also earned top prizes in The American Prize Competition for Opera, Operetta, and Art Song. She was awarded first place in the 2021 International Rocky Mountain Music Festival, based in Toronto, Canada, and was named a winner of the 2022 Montpelier Classical Recital Competition. Most recently, she advanced to Round Two of the 2023 BBC Cardiff Singer of the World Competition.

As a premed, Ms. Cooper completed her Bachelor’s Degree in French at Princeton University, where she first began to develop the foundation for her “mastery of French style” (Opera News) while conducting research for her undergraduate thesis on sacred themes in the mélodies, romances, and cantiques of Gabriel Fauré. She earned her Master of Music Degree in Vocal Performance and Pedagogy from Westminster Choir College, where she received the Gwynn Moose Cornell Endowed Award, given to the student who shows the most promise for a career in vocal performance.

In addition to performing, Ms. Cooper serves as volunteer Executive Assistant for Help!ComeHome!, a nonprofit dedicated to meeting the needs of under-served communities throughout the US in Jesus’ Name. Ms. Cooper is a regular volunteer with the organization, offering both her musical and administrative skills to further its mission. In her free time, Ms. Cooper enjoys gardening, playing cello, and being active outdoors. A former competitive gymnast, she was awarded top prizes at the annual Massachusetts State Championship meet while competing for the Gymnastics Academy of Boston.

—–

Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47 – Dmitri Shostakovich

BORN: September 25, 1906. Saint Petersburg, Russia

DIED: August 9, 1975. Moscow

COMPOSED: Begun on April 18, 1937, completed three months later, on July 20

WORLD PREMIERE: November 21, 1937. Evgeny Mravinsky conducted the Leningrad Philharmonic

US PREMIERE: April 9, 1938. Artur Rodzinski conducted the NBC Symphony

INSTRUMENTATION: 2 flutes and piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets and high clarinet in E-flat, 2 bassoons and contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, snare drum, triangle, cymbals, bass drum, tam-tam, bells, xylophone, 2 harps, piano, celesta, and strings

THE BACKSTORY: Shostakovich was nineteen when his professional life got off to a brilliant start with an amazing First Symphony, a work that soon spread his name abroad. But in 1936, his career ran aground. Stalin decided to see the composer’s much talked-about opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. He was scandalized, and in an article titled “Chaos Instead of Music” Pravda launched a fierce attack on Shostakovich. “Now everyone knew for sure that I would be destroyed,” Shostakovich recalled later. “And the anticipation of that noteworthy event—at least for me—has never left me.” He completed his Fourth Symphony, musically his most adventurous score to date, but withdrew it at the last minute. It was 1961 before he dared allow it to be played.

On April 18, 1937, Shostakovich began a new symphony, his Fifth. He completed it in July and presented it to the public in November. An unidentified reviewer called it “a Soviet artist’s reply to just criticism,” a formulation subsequently accepted by Shostakovich and indeed often attributed to him. We in the West read such a phrase with a certain embarrassment, and the story of an artist pushed into withdrawing a boldly forward-looking work and recanting with a more conservative one—for that the Fifth undoubtedly is—fits only too readily our perceptions of life in the Soviet Union. Nor do we comfortably accept the idea that “just criticism” couched in the largely meaningless spume of Pravda prose may actually have set the composer on a more productive path, and that “the road not taken”—the road of Lady Macbeth and the Fourth Symphony—was one well abandoned.

What was that road? The most striking features of the big works immediately preceding the Fifth Symphony are dissonance, dissociation, and an exuberant orchestral style. Though the chamber music of Shostakovich’s last years is based on more radical compositional means, the controversial opera and the Fourth Symphony still come across as the most “modern” of his works. We can imagine how, without Pravda’s “just criticism,” he might have traveled further along that road.

In any event, the completion of the Fifth Symphony and the jubilant embracing of it by the public constituted the most significant turning point in Shostakovich’s artistic life. The political rehabilitation was the least of it; just ten years later, at the hands of Andrei Zhdanov and the Central Committee of the Communist Party, Shostakovich was subjected to attacks far more vicious and brutish than those of 1936. (A second rehabilitation followed in 1958.) But Shostakovich found a language in which, over the next three decades, he could write music whose strongest pages reveal his voice as one of the most eloquent of his time—in, for example, the Leningrad, Eighth, Tenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth symphonies; the Third, Seventh, Eighth, Twelfth, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth string quartets; the Violin Sonata; and the Michelangelo Songs.

THE MUSIC: Shostakovich begins his Fifth Symphony with a gesture at once forceful and questioning, one whose sharply dotted rhythm stays on to accompany the broadly lyric melody that the first violins introduce almost at once. Still later, spun across a pulsation as static as Shostakovich can make it, the violins give out a spacious, serene melody, comfortingly symmetrical (at least when it begins), and with that we have all the material of the first movement. Yet it is an enormously varied movement. Across its great span we encounter transformations that totally detach thematic shapes from their original sonorities, speeds, and worlds of expression. The climax is harsh; the close, with the gentle friction of minor (the strings) and major (the scales in the celesta), is wistfully inconclusive. So convincing is the design that one can hear the movement many times without stopping to think how original it is (a quality it shares with the first movement of Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique). Shostakovich has discovered that “conservative” does not mean “conventional.”

The scherzo is brief, and it functions as an oasis between the intensely serious first and third movements. Its vein of grotesque humor owes something to Prokofiev and very much more to Mahler.

With the Largo’s first measures we meet a new warmth of sound. To achieve it, Shostakovich has divided the violins into three sections rather than the usual two, while violas and cellos are also split into two sections each. (One of the novelties of the Fifth Symphony is the economy of its orchestral style. In the Fourth Symphony, Shostakovich stints himself nothing; here, like those brilliant orchestral masters Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, he uses a complement by no means extravagant to unpack rich and forceful sonorities.) As in the first movement, Shostakovich proceeds by remarkable transformations and juxtapositions.

The Largo uses no brass at all, but brass is the sound that dominates the finale. This movement picks up the march music—the manner, not the specific material—that formed the climax of the first movement. But the purpose now is to express not threat and tension but triumph. “The theme of my symphony,” the composer declared in 1937, “is the making of a man. I saw man with all his experiences as the center of the composition. . . . In the finale the tragically tense impulses of the earlier movements are resolved in optimism and the joy of living.” Just before the coda, there is a moment of lyric repose, and Shostakovich’s biographer D. Rabinovich notes that the accompaniment, first in the violins, then in the harp, for the cello-and-bass recollection of the first movement is a quotation from a Shostakovich song of 1936. It is a setting of Pushkin’s Rebirth, and the crucial text reads: “And the waverings pass away/ From my tormented soul/ As a new and brighter day/ Brings visions of pure gold.” From that moment of reflection the music rises to its assertive final (and Mahlerian) climax.

It works just as it was intended to work, though many a listener may find that the impact and the memory of the questions behind this music are stronger than those of the answer. Solomon Volkov’s Testimony, the controversial “Shostakovich memoirs” published in 1979, includes a passage that seems to embody a truth about the closing moments of the Fifth Symphony. Volkov attributes these words to the composer: “Awaiting execution is a theme that has tormented me all my life. Many pages of my music are devoted to it. Sometimes I wanted to explain that fact to the performers, I thought that they would have a greater understanding of the work’s meaning. But then I thought better of it. You can’t explain anything to a bad performer and a talented person should sense it himself. . . . I think it is clear to everyone what happens in the Fifth. The rejoicing is forced, created under threat, as in Boris Godunov. It’s as if someone were beating you with a stick and saying, ‘Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing,’ and you rise, shaky, and go marching off, muttering, ‘our business is rejoicing, our business is rejoicing.’ What kind of apotheosis is that? You have to be a complete oaf not to hear that.” —Program notes by Michael Steinberg